August12

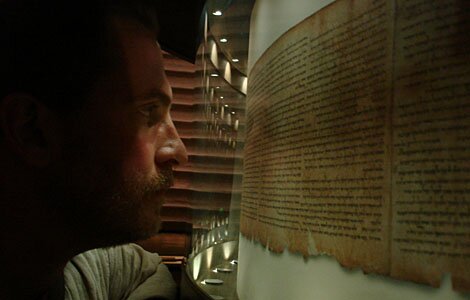

The science of textual criticism is a field of inquiry that has been invaluable to ascertaining the original state of the New Testament text. Textual criticism involves “the ascertainment of the true form of a literary work, as originally composed and written down by its author”. The fact that the original autographs of the New Testament do not exist , and that only copies of copies of copies of the original documents have survived, has led some falsely to conclude that the original reading of the New Testament documents cannot be determined. For example, Mormons frequently attempt to establish the superiority of the Book of Mormon over the Bible by insisting that the Bible has been corrupted through the centuries in the process of translation (a contention shared with Islam in its attempt to explain the Bible’s frequent contradiction of the Quran). However, a venture into the fascinating world of textual criticism dispels this premature and uninformed conclusion.

The task of textual critics, those who study the extant manuscript evidence that attests to the text of the New Testament, is to examine textual variants (i.e., divergencies among the manuscripts) in an effort to reconstruct the original reading of the text. They work with a large body of manuscript evidence, the amount of which is far greater than that available for any ancient classical author [NOTE: The present number of Greek manuscripts—whole and partial—that attest to the New Testament stands at an unprecedented 5,748 .

In one sense, their work has been unnecessary, since the vast majority of textual variants involve minor matters that do not affect doctrine as it relates to one’s salvation. Even those variants that might be deemed doctrinally significant pertain to matters that are treated elsewhere in the Bible where the question of genuineness is unobscured. No feature of Christian doctrine is at stake. Variant readings in existing manuscripts do not alter any basic teaching of the New Testament. Nevertheless, textual critics have been successful in demonstrating that currently circulating New Testaments do not differ substantially from the original. When all of the textual evidence is considered, the vast majority of discordant readings have been resolved. One is brought to the firm conviction that we have in our possession the New Testament as God intended.

The world’s foremost textual critics have confirmed this conclusion. Sir Frederic Kenyon, longtime director and principal librarian at the British Museum, whose scholarship and expertise to make pronouncements on textual criticism was second to none, stated: “Both the authenticity and the general integrity of the books of the New Testament may be regarded as finally established” (Kenyon, 1940, p. 288). The late F.F. Bruce, longtime Rylands Professor of Biblical Criticism at the University of Manchester, England, remarked: “The variant readings about which any doubt remains among textual critics of the New Testament affect no material question of historic fact or of Christian faith and practice” (1960, pp. 19-20). J.W. McGarvey, declared by the London Times to be “the ripest Bible scholar on earth” (Phillips, 1975, p. 184; Brigance, 1870, p. 4), conjoined: “All the authority and value possessed by these books when they were first written belong to them still”. And the eminent textual critics Westcott and Hort put the entire matter into perspective when they said:

Since textual criticism has various readings for its subject, and the discrimination of genuine readings from corruptions for its aim, discussions on textual criticism almost inevitably obscure the simple fact that variations are but secondary incidents of a fundamentally single and identical text. In the New Testament in particular it is difficult to escape an exaggerated impression as to the proportion which the words subject to variation bear to the whole text, and also, in most cases, as to their intrinsic importance. It is not superfluous therefore to state explicitly that the great bulk of the words of the New Testament stand out above all discriminative processes of criticism, because they are free from variation, and need only to be transcribed.

Writing in the late nineteenth century, and noting that the experience of two centuries of investigation and discussion had been achieved, these scholars concluded: “The words in our opinion still subject to doubt can hardly amount to more than a thousandth part of the whole of the New Testament”

THE AUTHENTICITY OF MARK 16:9-20

One textual variant that has received considerable attention from the textual critic concerns the last twelve verses of Mark. Much has been written on the subject in the last two centuries or so. Most, if not all, scholars who have examined the subject concede that the truths presented in the verses are historically authentic—even if they reject the genuineness of the verses as being originally part of Mark’s account. The verses contain no teaching of significance that is not taught elsewhere. Christ’s post-resurrection appearance to Mary is verified elsewhere (Luke 8:2; John 20:1-18), as is His appearance to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:35), and His appearance to the eleven apostles (Luke 24:36-43; John 20:19-23). The “Great Commission” is presented by two of the other three gospel writers (Matthew 28:18-20; Luke 24:46-48), and Luke verifies the ascension twice (Luke 24:51; Acts 1:9). The promise of the signs that were to accompany the apostles’ activities is hinted at by Matthew (28:20), noted by the Hebrews writer (2:3-4), explained in greater detail by John (chapters 14-16; cf. 14:12), and demonstrated by the events of the book of Acts ( McGarvey).

Those who reject the originality of the passage in Mark, while acknowledging the authenticity of the events reported, generally assign a very early date for the origin of the verses. For example, writing in 1844, Alford, who forthrightly rejected the genuineness of the passage, nevertheless conceded: “The inference therefore seems to me to be, that it is an authentic fragment, placed as a completion of the Gospel in very early times: by whom written, must of course remain wholly uncertain; but coming to us with very weighty sanction, and having strong claims on our reception and reverence”. Attributing the verses to a disciple of Jesus named Aristion, Sir Frederic Kenyon nevertheless believed that “we can accept the passage as true and authentic narrative, though not an original portion of St. Mark’s Gospel”. More recently, textual scholars of no less stature than Kurt and Barbara Aland, though also rejecting the originality of the block of twelve verses in question, nevertheless admit that the longer ending “was recognized as canonical” and that it “may well be from the beginning of the second century” (Aland and Aland). This admission is remarkable since it lends further weight to the recognized antiquity of the verses—what New Testament textual critic Bruce Metzger, professor Emeritus of New Testament Language and Literature at Princeton Theological Seminary, referred to as “the evident antiquity of the longer ending and its importance in the textual tradition of the Gospel” placing them in such close proximity to the original writing of Mark so as to make the gap between them virtually indistinguishable.

THE GENUINENESS OF MARK 16:9-20: THE TEXTUAL EVIDENCE

In light of these preliminary observations regarding authenticity, what may be said regarding the genuineness of the last twelve verses of the book of Mark? In arriving at their conclusions, textual critics evaluate the evidence for and against a reading in terms of two broad categories: external evidence and internal evidence. External evidence consists of the date, geographical distribution, and genealogical interrelationship of manuscript copies that contain or omit the passage in question. Internal evidence involves both transcriptional and intrinsic probabilities. Transcriptional probabilities include such principles as

1) generally the shorter reading is more likely to be the original,

(2) the more difficult (to the scribe) reading is to be preferred,

(3) the reading that stands in verbal dissidence with the other is preferable.

Intrinsic probabilities pertain to what the original author was more likely to have written, based on his writing style, vocabulary, immediate context, and his usage elsewhere.

Four Textual Possibilities

According to Metzger, the extant manuscript evidence contains essentially four different endings for the book of Mark:

(1) the omission of 16:9-20;

(2) the inclusion of 16:9-20;

(3) the inclusion of 16:9-20 with the insertion of an additional statement between verse 8 and verse 9 that reads: “But they reported briefly to Peter and those with him all that they had been told. And after this Jesus himself sent out by means of them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation”;

(4) the inclusion of 16:9-20 with the insertion of an additional statement between verses 14 and 15 which reads:

And they excused themselves, saying, “This age of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the truth and power of God to prevail over the unclean things of the spirits [or, does not allow what lies under the unclean spirits to understand the truth and power of God]. Therefore reveal thy righteousness now”—thus they spoke to Christ. And Christ replied to them, “The term of years of Satan’s power has been fulfilled, but other terrible things draw near. And for those who have sinned I was delivered over to death, that they may return to the truth and sin no more, in order that they may inherit the spiritual and incorruptible glory of righteousness which is in heaven.”

The fourth reading of the text may be eliminated as spurious. Meager external evidence exists to support it, i.e., only one Greek manuscript—Codex Washingtonianus. As Jack Lewis noted: “The support for the shorter ending is so inferior that no scholar would champion that Mark wrote this ending”. It bears what Metzger called “an unmistakable apocryphal flavor”. The statement does not match the style and grandeur of the rest of the section, leaving the general impression of having been fabricated. This latter point applies equally to the third ending since it, too, possesses a rhetorical tone that contrasts—even clashes—with Mark’s simple style.

The third ending represents a classic case of conflation—incorporating both verses 9-20 as well as the shorter ending—and may also be eliminated from consideration. In addition to internal evidence, the external evidence is insufficient to establish its genuineness. It is supported by four uncials that date from the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries, one Old Latin manuscript (which omits verses 9-20), a marginal notation in the Harclean Syriac, several Coptic (Sahidic and Bohairic) manuscripts and several late Ethiopic manuscripts. Besides being discredited for conflation, the third ending lacks sufficient internal and external evidence to establish its genuineness as having been originally written by Mark.

Omission

Ultimately, therefore, the question is reduced simply to whether verses 9-20 are to be included or excluded as genuine. Over the last century and a half, scholars have come down on both sides of the issue. Those who have questioned the genuineness of the verses have included F.J.A. Hort, B.H. Streeter, J.K. Elliott, and Bruce Metzger . On the other hand, those who have insisted that Mark wrote the verses have included John W. Burgon, F.H.A. Scrivener, George Salmon, James Morison, Samuel Zwemer, and R.C.H. Lenski.

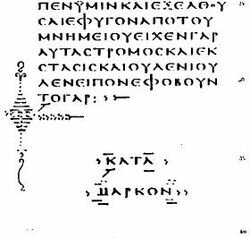

The reading of the text that omits verses 9-20 altogether does, indeed, possess some respectable support. The weightiest external evidence is the omission of the verses by the formidable Greek uncials, the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, which date from the fourth century. These two manuscripts carry great persuasive weight with most textual scholars, resulting in marginal notations in many English translations. For example, the American Standard Version footnote to the verse reads: “The two oldest Greek manuscripts, and some other authorities, omit from verse 9 to the end. Some other authorities have a different ending to the Gospel.” The New International Version gives the following footnote: “The two most reliable early manuscripts do not have Mark 16:9-20.” Such marginal notations, however, fail to convey to the reader the larger picture that the external evidence provides, including additional Greek manuscript evidence, to say nothing of the ancient versions and patristic citations.

Additional evidence for omission includes the absence of the verses from various versions:

(1) the Sinaitic Syriac manuscript,

(2) about one hundred Armenian manuscripts,

(3) the two oldest Georgian manuscripts that are dated A.D. 897 and 913.

Among the patristic writers (i.e., the so-called “Church Fathers”), neither Clement of Alexandria (A.D. 215) nor Origen (A.D. 254) shows any knowledge of the existence of the verses. [Of course, simply showing no knowledge is no proof for omission. If we were to discount as genuine every New Testament verse that a particular patristic writer failed to reference, we would eventually dismiss the entire New Testament as spurious. Though virtually the entire New Testament is quoted or alluded to by the corpus of patristic writers—no one writer refers to every verse.

Eusebius of Caesarea (A.D. 339), as well as Jerome (A.D. 420), are said to have indicated the absence of the verses from almost all Greek manuscripts known to them. However, it should be noted that the statement made by Eusebius occurs in a context in which he was offering two possible solutions to an alleged contradiction (between Matthew 28:1 and Mark 16:9) posed by a Marinus. One of the solutions would be to dismiss Mark’s words on the grounds that it is not contained in all texts. But Eusebius does not claim to share this solution. The second solution he offers entails retaining Mark 16:9 as genuine. The fact that he couches the first solution in the third person (i.e., “This, then, is what a person will say...”), and then proceeds to offer a second solution, when he could have simply dismissed the alleged contradiction on the grounds that manuscript evidence was decisively against the genuineness of the verses, argues for Eusebius’ own approval. The mere fact that the alleged contradiction was raised in the first place demonstrates recognition of the existence of the verses.

Jerome’s alleged opposition to the verses is even more tenuous. He merely translated the same interchange between Eusebius and Marinus from Greek into Latin, recasting it as a response to the same question that he placed in the mouth of a Hedibia from Gaul . He most certainly was not giving his own opinion regarding the genuineness of Mark 16:9-20, since that opinion is made apparent by the fact that Jerome included the verses in his landmark revision of the Old Latin translations, the Vulgate, while excluding others that lacked sufficient manuscript verification. Jerome’s own opinion is further evident from the fact that he quoted approvingly from the section.

Further evidence for omission of the verses is claimed from the Eusebian Canons, produced by Ammonius, which allegedly originally made no provision for numbering sections of the text after verse 8. Yet, again, on closer examination, of 151 Greek Evangelia codices, 114 sectionalize (and thus make allowance for) the last twelve verses.

In addition to these items of evidence that support omission of verses 9-20, several manuscripts that actually do contain them, nevertheless have scribal notations questioning their originality. Some of the manuscripts have markings—asterisks or obeli—that ordinarily signal the scribe’s suspicion of the presence of a spurious addition. However, even here, such markings (e.g., tl, tel, or telos) can be misconstrued to mean the end of the book, whereas the copyist merely intended to indicate the end of a liturgical section of the lectionary. Metzger agrees that such ecclesiastical lection signs constitute “a clear implication that the manuscript originally continued with additional material from Mark”.

The internal evidence that calls verses 9-20 into question resolves itself into essentially two central contentions: (1) the vocabulary and style of the verses are deemed non-Markan, and (2) the connection between verse 8 and verses 9-20 seems awkward and gives the surface appearance of having been added by someone other than Mark. These two contentions will be treated momentarily.

Inclusion

Standing in contrast with the evidence for omission is the external and internal evidence for the inclusion of verses 9-20. The verses are, in fact, present in the vast number of witnesses . This point alone is insufficient to demonstrate the genuineness of a passage, since manuscripts may perpetuate an erroneous reading that crept into the text and then happened to survive in greater numbers than those manuscripts that preserved the original reading. Nevertheless, the sheer magnitude of the witnesses that support verses 9-20 cannot be summarily dismissed out of hand. Though rejecting the genuineness of the verses, the Alands offer the following concession that ought to give one pause: “It is true that the longer ending of Mark 16:9-20 is found in 99 percent of the Greek manuscripts as well as the rest of the tradition, enjoying over a period of centuries practically an official ecclesiastical sanction as a genuine part of the gospel of Mark” . Such longstanding and widespread acceptance cannot be treated lightly nor dismissed easily. It is, at least, possible that the prevalence of manuscript support for the verses is due to their genuineness.

The Greek manuscript evidence that verifies the verses is distinguished, not just in quantity, but also in complexion and diversity. It includes a host of uncials and minuscules. The uncials include Codex Alexandrinus (02) and Ephraemi Rescriptus (04) from the fifth century. [NOTE: Technically, the Washington manuscript may be combined with these two manuscripts as additional fifth-century evidence for inclusion of the verses, since it simply inserts an additional statement in between verses 14 and 15.] Additional support for the verses comes from Bezae Cantabrigiensis (05) from the sixth century (or, according to the Alands, the fifth century—1987, p. 107), as well as 017, 033, 037, 038, and 041 from the ninth and tenth centuries. The minuscule manuscript evidence consists of the “Family 13” collection, entailing no fewer than ten manuscripts, as well as numerous other minuscules. The passage is likewise found in several lectionaries.

The patristic writings that indicate acceptance of the verses as genuine are remarkably extensive. From the second century, Irenaeus, who died c. A.D. 202, alludes to the verses in both Greek and Latin. His precise words in his Against Heresies were: “Also, towards the conclusion of his Gospel, Mark says: ‘So then, after the Lord Jesus had spoken to them, He was received up into heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of God” (3.10.5; Roberts and Donaldson, 1973, 1:426). It is very likely that Justin Martyr was aware of the verses in the middle of the second century. At any rate, his disciple, Tatian, included the verses in his Greek Diatessaron (having come down to us in Arabic, Italian, and Old Dutch editions) c. A.D. 170.

Third century witnesses include Tertullian, who died after A.D. 220, in his On the Resurrection of the Flesh (ch. 51; Roberts and Donaldson, 1973, 3:584), Against Praxeas (ch. 30; Roberts and Donaldson, 3:627), and A Treatise on the Soul (ch. 25; Roberts and Donaldson, 3:206). Cyprian, who died A.D. 258, alluded to verses 17-18 in his The Seventh Council of Carthage (Roberts and Donaldson, 1971, 5:569). Additional third century verification is seen in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. Verses 15-18 in Greek and verses 15-19 in Latin are quoted in Part I: The Acts of Pilate (ch. 14), and verse 16 in its Greek form is quoted in Part II: The Descent of Christ into Hell (ch. 2) (Roberts and Donaldson, 1970, 8:422,436,444-445). De Rebaptismate (A.D. 258) is also a witness to the verses. All seven of these second and third century witnesses precede the earliest existing Greek manuscripts that verify the genuineness of the verses. More to the point, they predate both Vaticanus and Sinaiticus.

Fourth century witnesses to the existence of the verses include Aphraates (writing in A.D. 337—see Schaff and Wace, 1969, 13:153), with his citation of Mark 16:16-18 in “Of Faith” in his Demonstrations (1.17; Schaff and Wace, 13:351), in addition to the Apostolic Constitutions (5.3.14; 6.3.15; 8.1.1)—written no later than A.D. 380 (Roberts and Donaldson, 1970, 7:445,457,479). Ambrose, who died A.D. 397, quoted from the section in his On the Holy Spirit (2.13.145,151), On the Christian Faith (1.14.86 and 3.4.31), and Concerning Repentance (1.8.35; Schaff and Wace, 10:133,134,216,247,335). Didymus, who died A.D. 398, is also a witness to the genuineness of the verses (Aland, et al., 1983, p. 189), as is perhaps Asterius after 341.

Patristic writers from the fifth century that authenticate the verses include Jerome, noted above, who died A.D. 420, Leo (who died ! 461) in his Letters (9.2 and 120.2; Schaff and Wace, 1969, 12:8,88), and Chrysostom (who died A.D. 407) in his Homilies on First Corinthians (38.5; Schaff, 1969, 12:229). Additional witnesses include Severian (after 408), Marcus-Eremita (after 430), Nestorius (after 451), and Augustine (after 455). These witnesses to the genuineness of Mark 16:9-20 from patristic writers is exceptional.

The evidence for inclusion that comes from the ancient versions is also diverse and weighty—entailing a wide spectrum of versions and geographical locations. Several Old Latin/Itala manuscripts contain it. Though Jerome repeated the view that the verses were absent in some Greek manuscripts—a circumstance used by those who support exclusion—he actually included them in his fourth century Latin Vulgate (and, as noted above, quoted verse 14 in his own writings). The verses are found in the Old Syriac (Curetonian) as well as the Peshitta and later Syriac (Palestinian and Harclean). The Coptic versions that have it are the Sahidic, Bohairic, and Fayyumic, ranging from the third to the sixth centuries. The Gothic version (fourth century) has verses 9-11. The verses are also found in the Armenian, Georgian, and Old Church Slavonic versions.

What must the unbiased observer conclude from these details? All told, the cumulative external evidence that documents the genuineness of verses 9-20, from Greek manuscripts, patristic citations, and ancient versions, is expansive, ancient, diversified, and unsurpassed.

Reconciling the Evidence

How may the conflicting evidence for and against inclusion of the verses be reconciled? In the final analysis, according to those who favor omission of the verses, the two strongest, most persuasive pieces of evidence for their position are (1) the external evidence of the exclusion of the verses from the prestigious Vaticanus and Sinaiticus manuscripts, and (2) the internal evidence of the presence of multiple non-Markan words. The fact is that the presumed strength of these two factors has led many scholars to minimize the array of evidence that otherwise would be seen to support the verses—evidence that, as shown above, is vast and diversified in geographical distribution and age. If these two factors are demonstrated by definitive rebuttal to be inadequate, the evidence for inclusion will then be recognized as manifestly superior to that which is believed to support exclusion. What, then, may be said concerning the two strongest pieces of evidence that have led many scholars to exclude Mark 16:9-20 as genuine?

Vaticanus and Sinaiticus

Regarding the first factor, it is surely significant that though Vaticanus and Sinaiticus omit the passage, Alexandrinus includes it. Alexandrinus rivals Vaticanus and Sinaiticus in both accuracy and age—removed probably by no more than fifty years. Why should the reading of two of the “Big Three” uncial manuscripts take precedence over the reading of the third? Are proponents staking their case in this regard on mere numerical superiority, i.e., two against one? Surely not, given the fact that the same scholars would insist that original readings are not to be decided by counting numbers of manuscripts. If sheer numbers of manuscripts decide genuineness, then Mark 16:9-20 must be accepted as genuine. Vaticanus and Sinaiticus should carry no more weight over Alexandrinus than that assigned by critics to the manuscripts that support inclusion on account of their superior numbers.

Vaticanus is technically, at best, a half-hearted witness to the omission of the verses. Though he considered the verses as spurious, Alford nevertheless offered an observation that ought to give one pause: “After the subscription in B [Vaticanus—DM] the remaining greater portion of the column and the whole of the next to the end of the page are left vacant. There is no other instance of this in the whole N.T. portion of the MS [manuscript—DM], the next book in every other instance beginning on the next column” (p. 484, emp. added). This unusual divergence from the scribe’s usual practice suggests that he knew that additional verses were missing. The blank space he left provides ample room for the additional twelve verses.

Interestingly, some have questioned the judgment of the scribe of Sinaiticus in his omission of Mark 16:9-20 on the grounds that he included the apocryphal books of the Shepherd of Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas (Aland and Aland,). Likewise, the scribe of Vaticanus included several of the Apocrypha in the Old Testament, as Sir Frederic Kenyon observed, “being inserted among the canonical books in B [Vaticanus—DM] without distinction”.

Those who support exclusion of Mark 16:9-20 have not been forthright in divulging that, as a matter of fact, Vaticanus and Sinaiticus frequently diverge from each other, with one or the other siding with Alexandrinus against the other. For example, the allusions by Luke to an angel strengthening Jesus in the Garden and the “great drops of blood” (Luke 22:43-44) are omitted by Vaticanus, while both Alexandrinus and Sinaiticus (the original hand) contain these verses. Luke’s report of Jesus’ statement on the cross (“Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they do”—Luke 23:34), is included by Alexandrinus and Sinaiticus (the original hand), but omitted by Vaticanus (p. 180). On the other hand, Vaticanus sides with Alexandrinus against Sinaiticus in their inclusion of the blind man’s confession and worship of Jesus (“‘Lord, I believe!’ And he worshipped Him”) in John 9:38 . It is also the case that both Vaticanus and Sinaiticus are sometimes separately defective in their handling of a reading. For example, in John 2:3, instead of reading “they ran out of wine,” the original hand of Sinaiticus reads, “They had no wine, because the wine of the wedding feast had been used up”—a reading that occurs only in Sinaiticus and in no other Greek manuscript. Many other instances of dissimilarities and dissonance between Vaticanus and Sinaiticus could be cited that weaken the premature assessment of the strength of their combined witness against Mark 16:9-20. [Cf. Luke 10:41-42; 11:14; Acts 2:43,44; Romans 4:1; 5:2,17; 1 Corinthians 12:9; 1 John 4:19.] Further, in some cases the UBS committee rejected as spurious the readings of both Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, and instead accepted the reading of Alexandrinus (e.g., Romans 8:2—“me” vs. “you”; Romans 8:35—“the love of Christ” vs. “the love of God” [Sinaiticus] or “the love of God in Christ Jesus” [Vaticanus]).

Summary of External Evidence

The following chart provides a visual summary of the external evidence for and against inclusion of Mark 16:9-20 for the first six centuries—since thereafter the manuscript evidence in favor of the verses increases even further (adapted and enhanced from Warren, 1953, p. 104). Observe that when one examines all three sources from which the text of the New Testament may be ascertained, the external evidence for the genuineness of the verses is considerable and convincing.

Non-markan style

Non-markan style

The second most persuasive piece of evidence that prompts some to discount Mark 16:9-20 as genuine is the internal evidence. Though the Alands conceded that the “longer Marcan ending” actually “reads an absolutely convincing text” , in fact, the internal evidence weighs more heavily than the external evidence in the minds of many of those who support omission of the verses. Observe carefully the following definitive pronouncement of this viewpoint—a pronouncement that simultaneously concedes the strength of the external evidence in favor of the verses:

On the other hand, the section is no casual or unauthorised [sic] addition to the Gospel. From the second century onwards, in nearly all manuscripts, versions, and other authorities, it forms an integral part of the Gospel, and it can be shown to have existed, if not in the apostolic, at least in the sub-apostolic age. A certain amount of evidence against it there is (though very little can be shown to be independent of Eusebius the Church historian, 265-340 A.D.), but certainly not enough to justify its rejection, were it not that internal evidence clearly demonstrates that it cannot have proceeded from the hand of St. Mark.

Listen also to an otherwise conservative scholar express the same sentiment: “If these deductions are correct the mass of MSS [manuscripts—DM] containing the longer ending must have been due to the acceptance of this ending as the most preferable. But internal evidence combines with textual evidence to raise suspicions regarding this ending” (Guthrie). Alford took the same position: “The internal evidence…will be found to preponderate vastly against the authorship of Mark” . Even Bruce Metzger admitted: “The long ending, though present in a variety of witnesses, some of them ancient, must also be judged by internal evidence to be secondary”.In fact, to Metzger, while the external evidence against the verses is merely “good,” the internal evidence against them is “strong”.

So, in the minds of not a few scholars, if it were not for the internal evidence, the external evidence would be sufficient to establish the genuineness of the verses. What precisely, pray tell, is this internal evidence that is so powerful and weighs so heavily on the issue as to prod scholars to “jump through hoops” in an effort to discredit the verses? What formidable data exists that could possibly prompt so many to discount all evidence to the contrary? Let us see.

Textual scholar Bruce Metzger summarized the internal evidence against the verses in terms of two factors:

(1) the vocabulary and style of verses 9-20 are deemed non-Markan,

(2) the connection between verse 8 and verses 9-20 is awkward, appearing to have been “added by someone who knew a form of Mark that ended abruptly with verse 8 and who wished to supply a more appropriate conclusion”.

The Connection Between Verse 8 and Verses 9-20

Concerning the latter point, one must admit that the evaluation is highly subjective and actually nothing more than a matter of opinion. How is one to decide that a piece of writing is “awkward” or “likely” to have been added by someone other than Mark? Tangible objective criteria must be brought forward to support such a contention if its credibility is to be substantiated. As support for the contention, Metzger notes

(1) that the subject of verse 8 is the women, whereas Jesus is the subject in verse 9,

(2) that Mary Magdalene is identified in verse 9 even though she has been mentioned only a few lines before in 15:47 and 16:1,

(3) the other women mentioned in verses 1-8 are now forgotten,

(4) the use of anastas de and the position of proton in verse 9 are appropriate at the beginning of a comprehensive narrative, but are ill-suited in a continuation of verses 1-8 .

Let us examine briefly each of these four contentions.

regarding the first point, a simple reading of the verses does not demonstrate a shift in subject from the women to Jesus. In actuality, the subject has been Jesus all along, but more specifically, His resurrection appearances. After pausing to relate specific details of the tomb incident involving three women (vss. 2-8), the writer returns in verse 9 to the subject introduced in verse 1—an enumeration of additional resurrection appearances, reiterating Mary Magdalene’s name for the reason that He appeared to her “first.”

Second, much is made of Mary Magdalene being identified in verse 9 though she had been identified already in 15:47 and 16:1. But if her name could be reiterated in 16:1—one verse after 15:47—why could it not be given again eight verses later? Has it escaped the critics’ notice that her name is also mentioned in full in 15:40—a mere seven verses before being mentioned again in 15:47? Yet, not one critic questions the genuineness of 15:47 or 16:1 though they redundantly identify Mary Magdalene again! The fact that there is more than one Mary in the text is sufficient to account for the repetition.

Third, it is also true that beginning in verse 9, the other women are not mentioned again. But, again, the reason for this omission is contextually obvious. Mary Magdalene is the one who spread the word about the resurrection to the others—“those who had been with Him” (vs. 10). It makes perfect sense that the focus would be narrowed from the three women to the one who performed this role.

Finally, the claim that the positioning of anastas de (“now when He arose”) and proton (“first”) are appropriate at the beginning of a lengthy narrative, but inappropriate in Mark 16 with only eleven verses remaining, is a claim unsubstantiated by Greek usage. It is not as if there is some observable rule of Greek grammar or syntax that verifies such a claim. It is simply the subjective opinion of one observer—albeit an observer who possesses a fair level of scholarly expertise. The term “first” (proton) has already been explained as appropriate since Mary Magdalene was the initiator of getting the word of the resurrection out to the others. Verses 9-14 are, in fact, intimately tied together in their common function of identifying resurrection appearances.

The precise construction “now when she arose” (anastasa de) is used by Luke (1:39) to introduce the narrative concerning Mary’s visit to Elizabeth—a section that extends for only eighteen verses (1:39-56). He used the same construction to introduce the narrative reporting Jesus’ visit to Simon (4:38)—lasting four verses (4:38-41)—the broader context actually extending previous to its introduction. Additional uses of the same construction (e.g., Acts 5:17,34; 9:39; 11:28) further verify that its occurrence in the concluding section of Mark is neither unusual nor “ill-suited.” How may one rightly claim that anastas de is inappropriate in Mark 16:9-20 if it is the only time Mark used it? Surely, what Mark would or would not have done cannot be judged on the basis of a single occurrence, nor should Mark’s stylistic usage be judged on the basis of what Luke or other users of the Greek language did or did not do. Is it possible or permissible that Mark could have legitimately used the construction intentionally only one time—without subjecting himself to the charge of not being the author? To ask is to answer.

Before leaving this matter of the connection between verse 8 and verses 9-20, one other observation is apropos. It is true that if Mark’s original book ended at verse 8, the book ended abruptly, leaving a general impression of incompleteness. However, the same may be said regarding the endings of both Matthew and Luke. Matthew reports the Jews’ conspiracy to account for the resurrection by bribing the guards to say the disciples stole away the body (28:11-15), and then shifts abruptly to the eleven disciples receiving the commission to preach (28:16-20). Likewise, Luke has two abrupt shifts in his final chapter. He reports the visits to the tomb by the women and Peter (24:1-12) and then suddenly changes to the two disciples traveling on the road to Emmaus (24:13ff.). Another takes place at the end of the Emmaus narrative (24:13-35) when Jesus suddenly appears in the midst of the whole group of disciples (24:36ff.). Yet no one questions the genuineness of the endings of Matthew and Luke. The final chapter of John (21) follows on the heels of John’s grand climax to his carefully reasoned thesis (20:30-31), and gives the general impression of being anti-climactic and unnecessary. Likewise, many of Paul’s epistles end abruptly, followed by detached and unrelated greetings and salutations. No one questions the genuineness of the endings of these New Testament books.

While Metzger does not accept verses 9-20 as the original ending of Mark, neither does he believe that the book originally ended at verse 8: “It appears, therefore, that ephobounto gar [“for they were afraid”—DM] of Mark xvi.8 does not represent what Mark intended to stand at the end of his Gospel” (1978, p. 228). But this admission that something is missing after verse 8 could just as easily imply that verses 9-20 constitute that “something.” Metzger concedes this very point when, after noting that “the earliest ascertainable form of the Gospel of Mark ended with 16:8,” he offers only three possibilities to account for the abrupt ending:

“(a) the evangelist intended to close his Gospel at this place;

(b) the Gospel was never finished; or, as seems most probable,

(c) the Gospel accidentally lost its last leaf before it was multiplied by transcription”.

If verses 9-20 are, in fact, attributable to Mark, its absence in some manuscript copies is explicable on the very grounds offered by Metzger against their inclusion, i.e., the last leaf of a manuscript was lost—a manuscript from which copies were made that are now being used to discredit the genuineness of the verses in question. If, on the other hand, verses 9-20 are not genuine, then the original verses that followed verse 8 have been missing for 2,000 years, and we are forced to conclude that the book of Mark lacks information that the Holy Spirit intended the world to have, but which they have been denied—an objectionable conclusion to say the least .

The Vocabulary and Style of Verses 9-20

But what about the style and vocabulary of verses 9-20? Are they “non-Markan”? Textual scholar Bruce Metzger insists that they are. Indeed, for those scholars who deem the verses spurious, the most influential factor—the most decisive piece of evidence—is the alleged “non-Markan vocabulary.” He defends his conclusion by referring to “the presence of seventeen non-Marcan words or words used in a non-Marcan sense”. Alford made the same allegation over a century earlier: “No less than seventeen words and phrases occur in it (and some of them several times) which are never elsewhere used by Mark—whose adherence to his own peculiar phrases is remarkable” . The reader is urged to observe carefully the implicit assumption of those who reject verses 9-20 on such a basis: If the last twelve verses of a document employ words and expressions (whether one or seventeen?) that are not employed by the writer previously in the same document, then the last twelve verses of the document are not the product of the original writer. Is this line of thinking valid?

Over a century ago, in 1869, John A. Broadus provided a masterful evaluation (and decisive defeat) of this very contention. Using the Greek text that was available at the time produced by Tregelles, Broadus examined the twelve verses that precede Mark 16:9-20 —verses whose genuineness are above reproach—and applied precisely the same test to them. Incredibly, he found in the twelve verses preceding 16:9-20 exactly the same number of words and phrases (seventeen) that are not used previously by Mark! The words and their citation are as follows: tethneiken (15:44), gnous apo, edoreisato, ptoma (15:45), eneileisen, lelatomeimenon, petpas, prosekulisen (15:46), diagenomenou, aromata (16:1), tei mia ton sabbaton (16:2), apokulisei (16:3), anakekulistai, sphodra (16:4), en tois dexiois (16:5), eichen (in a peculiar sense), and tromos (16:8). The reader is surely stunned and appalled that textual critics would wave aside verses of Scripture as counterfeit and fraudulent on such fragile, flimsy grounds.

Writing a few years later, J.W. McGarvey applied a similar test to the last twelve verses of Luke, again, verses whose genuineness, like those preceding Mark 16:9-20, are above suspicion . He found nine words that are not used by Luke elsewhere in his book—four of which are not found anywhere else in the New Testament! Yet, once again, no textual critic or New Testament Greek manuscript scholar has questioned the genuineness of the last twelve verses of Luke. Indeed, the methodology that seeks to determine the genuineness of a text on the basis of new or unusual word use is a concocted, artificial, unscholarly, nonsensical, pretentious—and clearly discredited—criterion.

CONCLUSION

For the unbiased observer, this matter is settled: the strongest piece of internal evidence mustered against the genuineness of Mark 16:9-20 is no evidence at all. The two strongest arguments offered to discredit the inspiration of these verses as the production of Mark are seen to be lacking in substance and legitimacy. The reader of the New Testament may be confidently assured that these verses are original—written by the Holy Spirit through the hand of Mark as part of his original gospel account.